In late May, the VLAB Works part of ASTC was acquired by Cadence, and as a result I am finally working in EDA for real. What a change! When I started working with the Simics simulator at Virtutech in 2002, we were at pains to distance ourselves from EDA. Now, almost 25 years later, I am working in one of the big three EDA companies.

Being a bit silly, you could compare my professional relationship with EDA to the typical story arc of a standard romantic comedy. Where two protagonists dislike each other when they first meet, but over time and with some drama, they have a change of heart and end up happily ever after.

We do Software, not Hardware

In the early days of Simics, we were at pains to distance ourselves from hardware design and EDA. Simulations coming out of the hardware design world were invariably too detailed, too slow, and too limited to run real software at scale in the way we could with our properly designed fast software-oriented simulator. If someone asked us, we were an (embedded) software tools company and not playing in the then-new virtual prototyping field. We sold to software developers, not hardware developers, and built models in a way appropriate for that use case.

Well, Maybe Hardware, Too

Still, hardware design was not all that far away. From the very start, we supported computer architects. However, that world is not really the same as “EDA”. Architects architect, and then their architecture is put into an actual implementation by implementers. Architects work with caches, pipeline stages, branch predictors, and such. The implementers code RTL and care about voltage and power and transistors and reaching clock frequency goals. We could honestly say we were not doing EDA.

However, to be honest, already in those early days we did come in contact with EDA and RTL. For example, I first saw a Palladium box (actually a whole set of them) on a customer visit in 2006. A few years later, we did some work with SystemC model integration since that is what we got from some IP providers (you can easily tell if someone is a software or hardware engineer by asking them what “IP” means).

My First DAC

In 2009, I attended my first Design Automation Conference (DAC). We were invited by Cadence to present on a panel, and I came in all cocky dismissing EDA simulation. We had something far better in Simics. Running large software stacks on a fast model was the thing to do, not hardware-accurate simulation for some tiny piece of firmware.

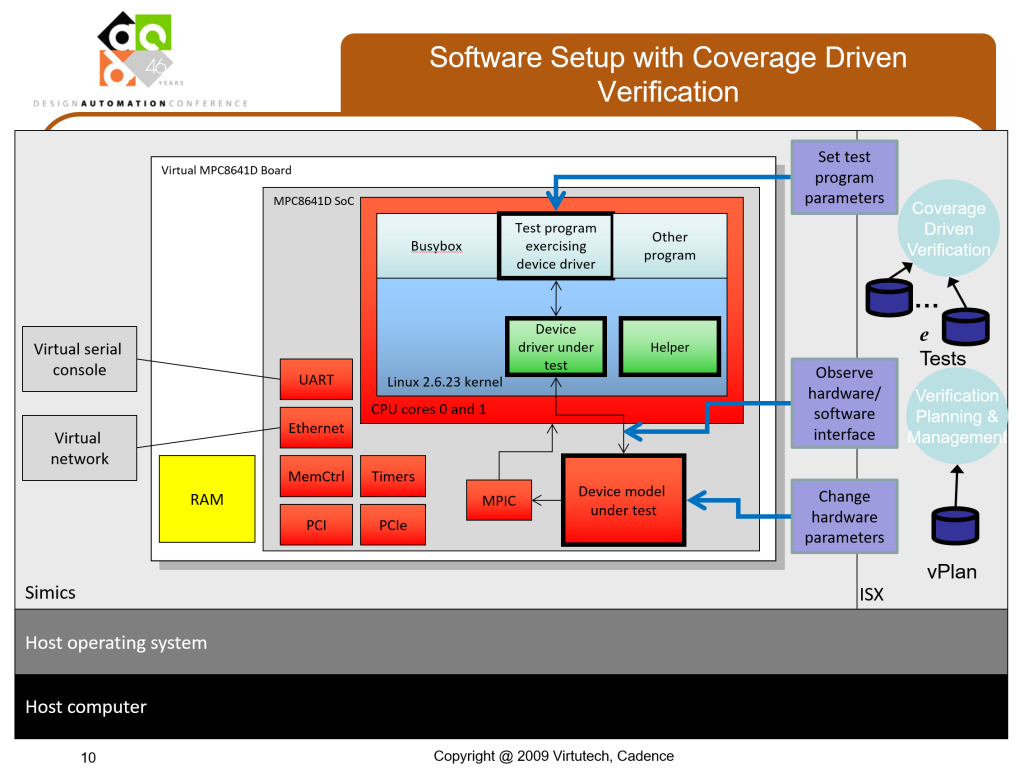

That said… we were at the DAC that year since we were collaborating with Cadence to see how we could combine the best of EDA and software. We were using the Cadence Incisive Software Extensions (ISX) to help do software driver validation – straddling the hardware-software line, using ideas from EDA like constrained random verification with software-oriented simulation.

DAC 2015

In 2015, I attended the DAC again. At this point, Simics had been acquired by Intel and us sales and marketing people were at Wind River. The DAC was expanding beyond RTL to pick the Systems and Software angle, and we got a good slot to present a SKYTalk in the main exhibition hall. So here I am, talking virtual platforms for embedded systems at the DAC. Pure virtual platforms for software development, nothing at all about hardware design or validation:

Moving to a Hardware Company

The year after, in 2016, I joined Intel “proper” and spent the next eight years working with the Simics team at Intel. Inside a hardware company, hardware design is rather hard to avoid. Internally at Intel, the Simics simulator was used for tasks related to hardware design – and in particular hardware validation.

As Simics models were developed earlier and earlier in the product life cycle, it made sense to use them to drive validation flows. Running software on a fast abstracted virtual platform, connected to RTL running on emulators or simulators (i.e., what we all know as VP hybrids).

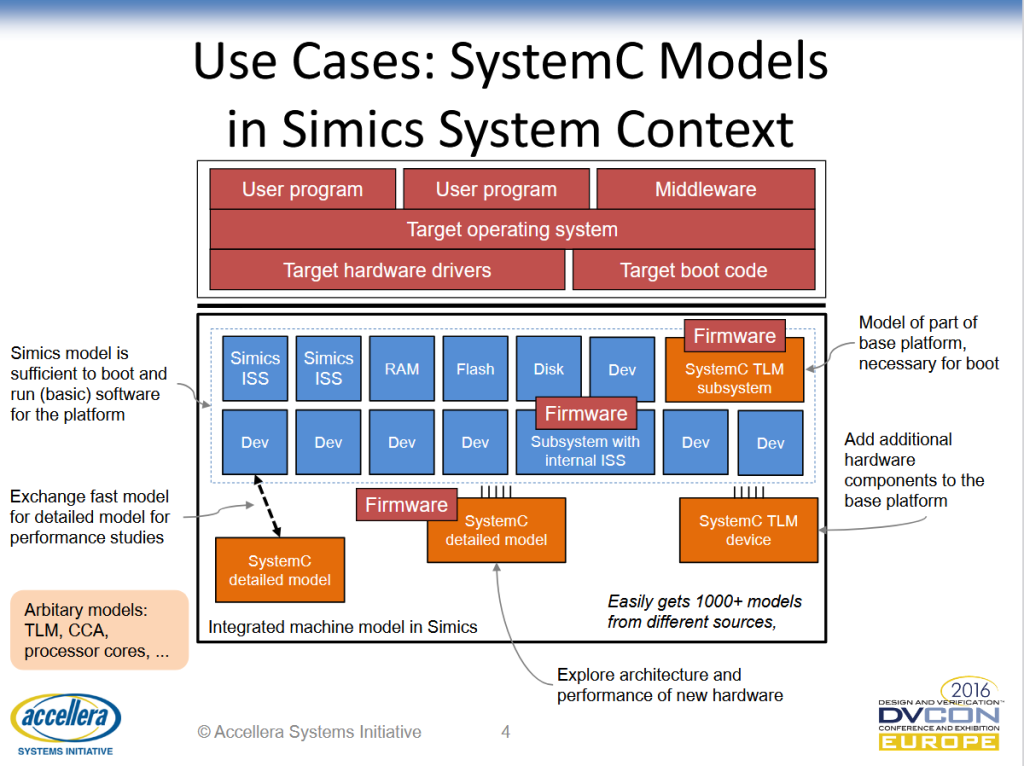

In addition, the Simics models were being extended with models from internal hardware design teams. These models would be integrated into an overall platform to get firmware running within the complete system software stack. As expected, many of these models would be quite detailed and thus slow, but they were there. And they might be built using tools that would be considered “EDA” – like SystemC.

We published a paper about the (second variant of) SystemC model integration into Simics at DVCon Europe 2016. After that, I have been a regular at DVCon Europe, even joining the organizing committee in 2022. Being at Intel, it was quite natural to interact with the EDA space.

Happily Ever After

Today, it is clear that virtual platform technology is inextricably linked to EDA.

Of course, there is a spectrum of abstractions suiting different use cases, and some of those are the not-EDA approach we took in Simics back in 2002. But all tools have hooks to bring in hardware models and connect to RTL validation flows. It is just unavoidable, as software has become an inextricable part of any digital product. And doing software after the silicon is completed is a non-starter.

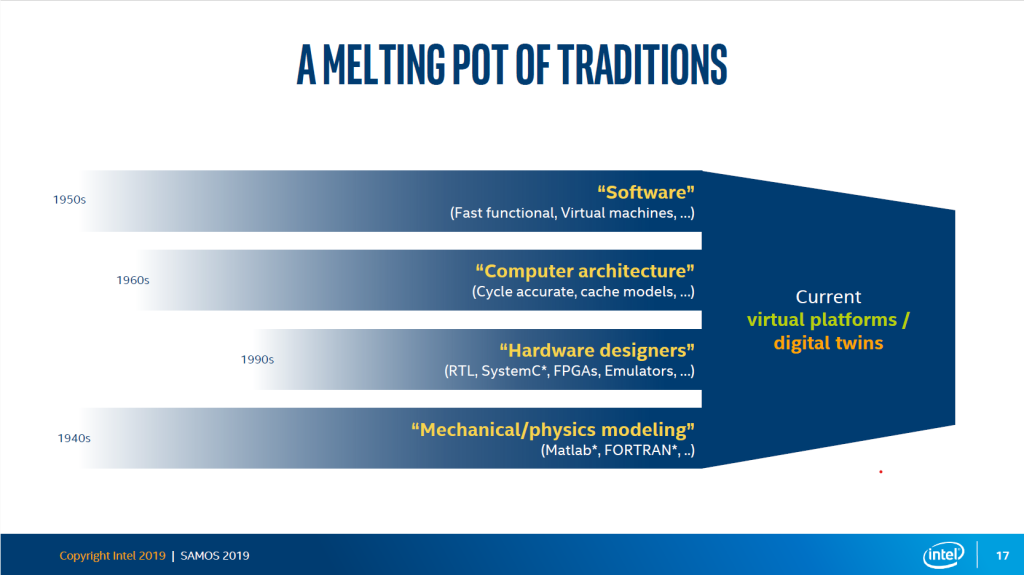

I think we are also seeing a merging of multiple simulator development paths or traditions:

I drew the above picture for a keynote talk in 2019, showing how different types of simulation have come together to form digital twins, virtual prototypes, and virtual platforms today. Not every setup will use all or even multiple types of simulators, but any systems project is likely to use them all at some point in their development.

In 2025, I cannot deny that I have been working with EDA for a long time and, after joining Cadence, in EDA. I couldn’t avoid EDA, and EDA couldn’t avoid me.

love your journey in the electronics industry